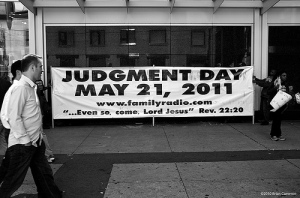

Nothing happened. May 21, 2011 came and went just like any other day, despite the highly publicized prediction of Family Radio host Harold Camping that Jesus would return at 6pm local time and begin his rapture cycle around the earth. Instead of allowing this failed prediction to challenge his “hidden meaning” method of decoding the Bible, however, Camping rationalized that his calculations must have been off by a few months and that the actual apocalypse would take place on October 21 of that year. It wasn’t until March 2012 that Camping admitted he had been mistaken. Needless to say, if Leon Festinger hadn’t already published his study on cognitive dissonance half a century ago, someone surely would have been inspired to do so by this tragic episode.

Most Christians recognize the overt absurdity of Camping’s method of pulling hidden predictions out of Scripture. Only isolated fringe groups do that. On a much more subtle level than Camping, however, there is a prevalent tendency amongst the faithful to rationalize “unfulfilled prophecies” into the future. In fact, I would argue that this is the whole foundation of the futurist system of biblical interpretation. Camping attempted to preserve faith in his failed prediction by pushing it into the future; the futurist system turns this thinly veiled coping mechanism into a controlling principle when dealing with biblical prophecy.

Before we go on, however, I should clarify exactly what I’m talking about. In theological parlance, labels like “futurism” and “preterism” speak of a systematic priority that governs the way someone approaches biblical prophecy in general, or at least predominately. It is the particular systematic priority of futurism, and the logic which regularly undergirds it, which is the object of my criticism in this post. My argument does not preclude the possibility of any future interpretations, just the underlying logic of the futurist system, which in many cases has no other reason for saying that a passage is concerned with our future except that the past event to which it seemed to be looking forward did not play out exactly like the passage said it would. My criticism here could just as easily be applied to preterism, but that’s a subject for another day.

I used to take a consistently futurist approach to biblical prophecy. Whether it was Jeremiah’s lengthy oracle against Babylon in Jeremiah 50-51, Ezekiel’s panoramic vision of a rebuilt temple in Ezekiel 40-48, Jesus’ Olivet Discourse in each of the Synoptic Gospels, or John’s vision of the “Beast” and the “Harlot” in Revelation 17-19, I would always assume a literal interpretation of the text, and, because of my faith in its inspiration, I would always assume it referred to events still to come in the future, thousands of years after it was given, since it obviously hadn’t yet been fulfilled. A futurist reading, I thought, was the only faithful approach to such passages.

It took me several years to realize that my commitment to futurism was ironically based in the same rationalizing tendency as the allegorical school which I so strongly opposed. As different as those two approaches are in their outworking interpretations, the same controlling agenda which drove Origen and Augustine to spiritualize whole books of the Old Testament drove me to project every seemingly unfulfilled prophecy into the future. That rationalizing tendency, that controlling agenda, arose from the psychological need to erase discrepancies when newly perceived data (in this case, the apparent non-fulfillment of prophecies with explicitly time-sensitive content) conflicted with my strongly held beliefs (in this case, my faith in the authority of Scripture). The challenge I faced, however, was in trying to reconcile my futurism with a consistently historical reading of Scripture. It was because I could not, on the last analysis, bring myself to change the meaning of the text into something it never intended to say that I could no longer in good conscience remain a futurist.

There are two primary questions that the student of biblical prophecy must face. First, what does this prophecy mean? Second, has this prophecy been fulfilled? Both questions are important, but the integrity of our exegesis depends largely on keeping them separate and in their proper order. The biggest problem with most interpreters is that they let the question of fulfillment drive the question of meaning, instead of first addressing the question of meaning on its own terms. This is particularly true for those interpreters who are committed to a high view of Scripture. “The Olivet Discourse has to be about the future,” so the line often goes, “because it obviously wasn’t fulfilled in the past, and we know that Jesus couldn’t have been wrong.” But if we really believe in the authority of Scripture, then we should always assume that the interpretation arrived at through the inductive process will be the one with the most Spirit-filled application for our own time, regardless of our expectations.

The point here is not that we have to give up a high view of Scripture, but that we can’t let our prior commitments about the nature of Scripture determine in advance what the text can and cannot say. Of course this then puts us in the uncomfortable position of entertaining the possibility that some biblical prophecies simply didn’t come to pass. But unless we deal with such possibilities openly and honestly, our belief in the authority of Scripture becomes only a lame attempt at reducing our own cognitive dissonance.

As self-evident as this is, however, it’s remarkable how often it is either forgotten or ignored. The besetting sin of futurist interpreters, in their approach to prophetic passages throughout Scripture, is their deeply felt need to liberate the text from the embarrassing constraints of its own time. Such interpreters are not really interested in understanding what the text would have meant in its original historical context, but only in what it can be seen to mean for our own time. Thus, where Jeremiah pronounces a retributive judgment on Babylon and its king for their treatment of Judea, or where Ezekiel foresees a rebuilt temple after the regathering of his people from exile, or where Jesus predicts the son of man’s coming within the generation of his listeners, or where John predicts the sudden destruction of the great city which reigned over the kings of the earth in his own day—in all of these cases futurists feel the need to lift the referent of the prophetic text out of the immediate future of the original audience and into our future, in order to thereby save the text from the reproach which, upon the assumption of a literalist reading, would undoubtedly come upon it. Where was the bloody, violent, and absolute destruction which Jeremiah pronounced on Babylon? Where was “the coming of the son of man” in the lifetime of Jesus’ listeners? Where, indeed, was the fulfillment of all of the cataclysmic events foreseen by John in the book of Revelation?

When confronted with such unpleasant difficulties, futurists see two basic options: either (a) we admit that the text was uninspired, unathoritative, and glaringly wrong in its predictions about the future, or (b) we project it into the future and thereby protect its inspired status. So like Peter in Gethsemane, we unsheathe our swords and cut away. But like Peter, we fail to consider that there might be other alternatives besides the two extremes of denying our Lord or plugging our ears and fighting to save face. Are we sure we understand what the prophecies are all about? As a true post-Enlightenment Westerner, I used to assume a literalist reading of all biblical prophecy, giving very little room for metaphorical, symbolic or hyperbolic modes of speech; but I have since come to realize that such a commitment rarely does justice to the intention of the biblical prophets themselves. Jesus’ intention with respect to “the coming of the son of man” is a prime example of this. If we endeavor to understand Jesus’ words historically, then the rigid literalism of the futurist school appears at once grossly anachronistic and impossibly constricting.

Before we can even contemplate the possibility of other alternatives, however, we must face the music; we must give proper recognition to the text’s fundamental rootedness in its own time, whatever the outcome. When prophecies with historical detail and context such as Jeremiah 50-51 aren’t “fulfilled” in a rigidly literal, meticulous sort of way, the futurist assumption is that we should simply lift the text from its stated context and postulate a future one-to-one fulfillment. But if our primary aim is to handle such passages with exegetical integrity, as indeed it should be, then we simply cannot ignore the specific indicators of historical context and authorial intent. Jeremiah was not speaking against a nation that did not exist at that time or a king who had not yet been born. No, he speaks against a contemporary nation and its king for the evil which they had committed against Judah in the years 599-586BC, which Jeremiah himself witnessed and documented at length. The whole point of the passage, resting on the law of retribution, is that the violence and destruction which Nebuchadnezzar dealt to Israel would come back upon his own head (cf. 50:17-18, 29; 51:34-35). Exegesis demands this conclusion.

To claim, on the other hand, that this passage must speak of a future period, because several details of the prophecy did not play out exactly as described, is a decidedly eisegetical move. Instead of reading the text inductively and asking the appropriate questions of authorial intent and public meaning, the futurist view relies entirely on a deductive process of elimination, looking outside of the prophecy and imposing its own set of criteria for what it can and can’t mean based entirely on what did and what did not in fact occur thereafter. Such an abstract a priori has absolutely nothing to do with what the text itself would have meant in the world in which it was written, but has everything to do with maintaining a particular theological construct despite all the evidence to the contrary. If it didn’t happen, just transpose it into the future. It must not have meant what it said. The original audience probably didn’t get it. The prophet himself probably didn’t get it. But we get it.

By thus lifting the passage out of its own world of meaning and supplying another we lose all anchorage with the only context in which the text itself makes sense. This is not exegesis. Genuine exegesis is committed to listening to the text on its own terms—and if history does not play out exactly like the passage said it would, then we should ask the question why. Perhaps we’ve misunderstood the content of the prophecy, or perhaps something transpired afterwards which altered the terms of the prophecies’ fulfillment. Remember, the God of the prophets regularly speaks about what will happen if humans presently respond in such and such a way; he does not speak in an abstract vacuum of time and space about what will happen regardless of the present human response. The whole point of prophecy is to produce a response, a change; and if all men responded then no prophecy of judgment would ever come to pass (cf. Jer. 18:7-11).

In other words, we are not bound to reject the truth of biblical prophecy by remaining faithful to the text. But then, even if we can’t find a solution to every text in which this problem appears, it’s a much more honest display of faith in the authority of Scripture to first take the text at its own terms, and then to say “I don’t know” in reply to the question of fulfillment, than to try to save face by suggesting the text actually refers to something else, something easier to get our hands around. That’s not true faith; that’s doubt in disguise. And that is why I am no longer a futurist.

I love you.

Well Said – Semper Reformanda.

Well spoken, Matt. Happy Western Easter to you and Becky!

This is really good…

Hey, you were listening in hermeneutics class, after all!!! I am always concerned when students launch into systematic theology BEFORE they really get a good understanding of inductive Bible study. Indoctrination into one system of belief before understanding how to really study scripture will always yield immature / partially formed fruit. Related to the specifics of Biblical Prophecy, I often think of it as skipping stones across the surface of a lake. The first skip is the most important one – sometimes the stone stops there and plunges into the depths of the lake at that point. Sometimes the stone skips only once, sometimes many skips result. We simply can’t expect every “stone of prophecy” to behave the same way. The original context (first skip), however, is critical to understanding the behavior of the individual stone whether it plunges, skips only once, or multiple times. One other factor that you didn’t address here is how the NT writers understood the skipping process of each stone of prophecy they quoted. That is for another article, though. Blessings, Matt!

Hey Tom, thanks for the comment! I sure hope something stuck, after taking your hermeneutics class three times! 🙂

I like the analogy of “skipping stones” more than the one you regularly hear about the “mountain peaks” – because it seems more flexible and adaptable to the wide range of prophecy throughout Scripture. Personally, I tend not to think that the prophets were actually referring to multiple, seperate events with equal intention. In many cases, I think it’s mostly a matter of interpretation versus application, and readers wanting to give their application a higher status as interpretation. It’s definitely a subject for another blog post, but I lean towards thinking that in many cases where there is a “farther mountain peak” in view, it is only as the “vehicle” (i.e. the imagery) through which the prophet describes the “tenor” (i.e. the referent) of his prophecy about the near future. In other words, the prophets sometimes used eschatological language consciously as a metaphorical lens when referring to something else.

The common usage of the “day of the Lord” throughout the OT the best example of this phenomenon. We can tell from the first occurrence of the phrase, in Amos 5:18-20, that it had already carried a popular meaning within Israel, since the prophet uses it polemically. It seems that Amos’ contemporaries longed for the day of the Lord as the climactic moment in Israel’s history, the time when YHWH would act on their behalf and bring victory over their enemies. But because of their unfaithfulness, Amos turns that expectation around and speaks of the “day of the Lord” as a time of judgment for Israel and not victory. In other words, he holds up Israel’s eschatological expectation of judgment against their enemies as a lens for them to understand God’s present judgment against them. And yet, because Amos does not see God’s judgment against Israel as the final word, but still affirms a redemptive hope beyond that judgment, we can tell that he did not truly think of that judgment as the day of the Lord in the ultimate and established sense of the phrase. Hence, he uses it as an eschatological metaphor.

I think similar language is used throughout the prophets when referring to immediate socio-political events. I wouldn’t suggest this as a holistic hypothesis for all prophetic language, but rather as an explanation for some instances of prophetic language on a strictly case-by-case basis. If I could put my view in a series of propositions, it would look something like this:

1. The biblical writers believed that human history was moving towards a goal, a time when all things would be made right, a time when sin would be dealt with, when evil would be judged, and when God’s people would be redeemed and vindicated.

2. The biblical writers often used end-of-the-world language to refer to this climactic expectation, but they did not believe in a literal end of the material universe. Rather, in contrast with later Greek thought, their hope was very concrete and this-worldly. At the very least, then, such language is hyperbolic.

3. Some biblical writers also used this type of language metaphorically to refer to that which they knew well was not the final or climatic goal of history, because they perceived typological associations between the present referent and the final goal and thereby invested the former with the meaning of the latter.

4. It is appropriate then to speak in these instances of prophetic language carrying an eschatological excess beyond its primary referent, as the imagery itself evokes the final goal which is embedded in the Judeo-Christian expectation.

I think this account answers for a regular phenomenon in biblical prophecy that is often explained on a popular level through the category of “dual fulfillment” – but I think it has the advantage of being much more sensitive to the way biblical language and imagery actually works. The fact that there is “eschatological excess” in the language of these prophecies does not change the fact that the referent is a near impending and/or present matrix of events. And while that excessive language does collectively paint a picture of the ultimate end, through the broad brush strokes of judgment and vindication, of tribulation and deliverance, this language should not be taken as giving photographic clarity about the end. The picture is impressionistic and evocative, not photographic. Does that make sense?

What a clear and compelling argument! What food for thought! And thanks for communicating without a hint of divisiveness or sarcasm.

Beau, to your brief remark I say “Amen”. The reality of “without a hint of divisiveness or sarcasm” points to pure heart I believe. Which, at the end of the day, is what God truly looks at. I don’t pretend to always understand the language or the conclusions that Matt draws… but I DO know the HEART behind the man. And it is without guile. Proud, as always, to call him my son!

As a Preterist, how do you interpret Zechariah 12-14? Is this about 70 AD? If so, why does it talk about God coming to rescue Jerusalem?

I don’t really consider myself a preterist, actually. Just as the label “futurist” suggests a systematic priority towards the final period of history, “preterist” tends to suggest an opposite systematic priority towards AD70. The Olivet Discourse is a cornerstone of preterism, yes, but someone who takes the title “preterist” as a self-designation generally carries the same reading beyond Mark 13 and its parallels to Revelation, Daniel, etc, give or take. Personally, while I do think that’s what the Olivet Discourse is about, I don’t try to fit all other prophecy into that – I don’t think it’s a primary emphasis in Revelation, and I don’t think it’s in view at all in Daniel – and for this reason, I don’t use the term “preterist” as a self-designation.

Regarding Zechariah 12-14: in order to understand my approach to that passage it might be helpful to read the two posts I’ve written on interpreting OT prophecy in general (which you can find here and here). Basically I take a two-fold approach: first, acknowledging what an Old Testament prophecy would have meant in it’s original covenantal context, but then recognizing the discontinuity between what the prophet saw and what will now come to pass (and/or, perhaps, has come to pass) under the new covenant because of the death and resurrection of Jesus. Applying this to your question, I don’t think Zechariah 12-14 was intended as or would have been understood as a messianic passage in its original context. Rather, I think it stands next to many other OT passages about YHWH’s return to Zion, of a New Exodus, etc. Of course, because the early church believed that Jesus was the embodiment of YHWH, they naturally re-read all of these “coming” passages through a new christological lens; but (strictly speaking) I do not think that such an understanding was in view for Zechariah himself.

It seems to me that a futurist approach, by contrast, is forced to disregard a thoroughly historical reading of the passage in the interest of fitting it one-for-one into a new covenant, future fulfillment. But the problem is that it just doesn’t fit. Take, for instance, the way MB dealt with the “Canaanites” of Zechariah 14:21 in his seminar last weekend. The text says, “In that day there shall no longer be a Canaanite in the house of the Lord of hosts.” A proper historical reading would take this text along side other similar passages (like, e.g., Obadiah 17-21) as a typical OT perspective, and it would not try to spiritualize it through an incompatible NT lens. But that’s exactly what Mike does when he says that “Canaanite” there speaks of “a type of behavior not a particular bloodline”. Of course, if we aim to read the text on its own terms, it really does appear to speak of a particular bloodline, just like Ezekiel 44:9 speaks of the “foreigner” and the “uncircumcised in flesh” not being allowed to enter into the sanctuary of the new temple. The irony here is that Mike’s argument for the futurist reading is that it doesn’t require one to spiritualize the text like amillennialists are supposedly forced to do, but then that’s exactly what he is forced to do in order to fit the details of the text into the framework of a new covenant fulfillment. It’s because I agree with the ideal to which Mike appeals – of a non-spiritualized, historical-grammatical reading of the text on its own terms – that I ultimately cannot espouse a futurist reading of Zechariah 12-14.

What about Mark of the Beast? Can’t help but notice you’ve never addressed this subject. For me the preterist slant falls totally apart here, and allegiance to truth/hermeneutics becomes flexible.

Max, I think you may have misunderstood my point in this post. If you are curious how a contemporary-historical approach would interpret the “mark of the beast” in Revelation 13, though, my friend Mark Edward has written a good study on the subject, at the link below.

http://gladdening-light.blogspot.com/2013/01/revelation-29-six-hundred-sixty-six.html

Thanks, I see what you are saying there, I’ve seen similar online, but how would that approach deal with the other things we know about the mark and Nero?

Rev 14:11 And the smoke of their torment will rise for ever and ever. There will be no rest day or night for those who worship the beast and its image, or for anyone who receives the mark of its name.

Revelation 16:2 The first angel went and poured out his bowl on the land, and ugly, festering sores broke out on the people who had the mark of the beast and worshiped its image.